Other People's Baseless Hatred

How many political commentators miss the point of Judaism's day of mourning—and how we can recover it

Today is Tisha B’av, the day of mourning which commemorates numerous national tragedies in Jewish history, beginning with the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem. It’s an occasion with much to teach us, whether we are Jewish or not, but whose lessons are often misunderstood. Here is my effort to recover one of them.

“What do you think about baseless hatred?” This is not the sort of question most academics are used to being asked, let alone by reporters. But at this time of year, when Jewish tradition mourns the destruction of the First and Second Temples, it’s exactly the sort of query regularly put to Hebrew University’s Isaiah Gafni, a preeminent historian of rabbinic Judaism. That’s because the rabbis of the Talmud famously attributed some of these tragedies to sin’at chinam, or baseless hatred among Jews, which brought about divine punishment.

Now, Israeli journalists are not really interested in Gafni’s scholarly opinion of the term. “What they’re trying to say,” he observes in one of his lectures, “is that there’s as much sin’at chinam now as there was then.” In other words, the reporters want to use Gafni and his academic credentials to bolster their critique of contemporary Israel and its people, who are deeply divided along factional lines. But he refuses to play along. “I’ve really gotten sick of that question, and I usually try to answer now saying: ‘I really don’t know, because I am not plagued with sin’at chinam. The people that I hate really deserve it!’” He chuckles. “Usually they kind of hang up on me. This is not what they wanted.”

But Gafni’s seemingly unserious riposte makes a serious point. “No one is ever guilty of sin’at chinam,” he notes. “It’s always the other person that’s guilty of hating me.” Our own animosities are always justified in our eyes; it’s only hatred harbored by others that we consider groundless. A quick glance at modern political invocations of the charge of sin’at chinam perfectly illustrates Gafni’s principle: for many Jewish ideologues, sin’at chinam is the perpetual sin of other people, specifically those they disagree with.

“The true face of the fascist purveyors of sin’at chinam,” declares a blogger for the London Jewish Chronicle, are “the settlers and their great pretender friends.” Of course, for a sympathizer of the Israeli settler movement, sin’at chinam was evident when “those Jews who did move trailers onto hills within their existing towns were dislodged by the IDF.” In the eyes of hawkish pro-Israel advocates, the dovish group J Street promulgates baseless hatred. Yet some of the liberal lobby’s supporters believe they have found the true purveyors of sin’at chinam: right-wing Zionist organizations. “We will show that sin’at chinam will soon be a way of the past if our voices have anything to say about it!” proclaim the progressive Women of the Wall, who advocate for women’s religious rights at the Western Wall. “Stop practicing sin’at chinam, baseless hatred, and you will find it mysteriously vanishes. It’s easy to have peace and unity — just pray with us, and don’t try to change us,” admonish their conservative opponents, a group called Women for the Wall. And so on.

Obviously, I have my own sympathies in each of these debates. But to indulge them here would be to miss the point. Nothing could be further from the spirit of Tisha B’av, today’s national day of mourning, than using its moral vocabulary to impugn others. In fact, when it comes to explaining the root causes of the destruction of the Temple, the Talmud teaches the very opposite lesson: that we must root out baseless hatred within ourselves.

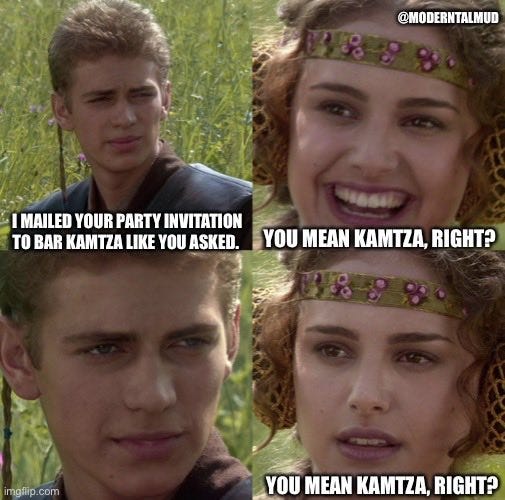

“The destruction of Jerusalem came about through a Kamzta and a Bar Kamzta,” declares the Babylonian Talmud. A “certain man,” the rabbis recount, had a friend named Kamtza and an enemy named Bar Kamtza. This individual threw a party, and sent his servant to invite the first man. But the messenger erred and instead brought the host’s soundalike foe, Bar Kamtza.

And so, in full view of the many rabbis in attendance, the host ejected Bar Kamtza from the festivities, even after he offered to pay for the entire party rather than face such public humiliation. Embittered by this experience, and particularly incensed at the rabbis who stood by while he was shamed, Bar Kamtza slanderously denounced the Jews to the Roman emperor, setting in motion the conquest of Jerusalem.

What’s striking about this origin story is that it apportions blames to the people recounting it, namely, the rabbis who did not intervene at the party. The host of the affair, the ostensible culprit, is never even named. While the Talmudic sages could easily have pinned the entire episode on him, they chose instead to share the blame themselves. National tragedy, in the traditional Jewish understanding, is not an opportunity to assert our own sense of superiority, but to foster a spirit of self-critique. As the Mussaf prayer every new month reminds us, “because of our sins, we were exiled from our land.”

On Tisha B’Av, of all days, we are not meant to point to flaws outside ourselves, however apparent they may be, but rather to examine those within. After all, we can never truly know the minds and motivations of others. The only baseless hatred we can diagnose is our own.

This piece is a revised version of one that appeared in Tablet in 2013.