Q&A with Adam Serwer

“The news is what people have forgotten, not just what people don’t know yet.”

A reminder that we’ll be doing our monthly Ask Me Anything for paid subscribers tomorrow. Sign up or upgrade your subscription to join us.

I often get asked who I read and why. It’s a good question, especially with so much material out there competing for attention. My answer is this: I try to read people who tell me something I didn’t know, even when I don’t agree with what they said. There are lots of writers who do an elegant job telling me things I already know or believe. There are far fewer who teach me something new every time. Adam Serwer of The Atlantic is one of those writers.

He is also a day 1 subscriber to this newsletter (#35, I checked!), and someone whose thinking has shaped my own. Many know him for his writings on Trump and race in America, but do not know that he is also an incisive thinker on questions of Jewish community and identity, and someone for whom Judaism is an inextricable part of his life and work.

On the occasion of the publication of his now New York Times bestselling book, The Cruelty is the Point, we sat down to chat about everything from the origins of antisemitism, to the untold story of American Jewry’s debate over slavery, to whether Jesus Christ did karate.

YR: My first question is actually not about any specific piece in the book, but about your intellectual method, which is the thing that draws me to your writing again and again. In essence, you consult the past in order to understand the present. You are constantly situating the arguments you’re making about where we should go in discussions of where we’ve been. And I think in an ideal world, a lot of journalism would do that. But in practice, we live under incredible industry pressures and deadlines, and this is just extremely difficult. So I’m curious about how you approach that. What does it look like to study the things you study, and then figure out how you want to write about them?

AS: I spend a lot of time reading books on subjects that I’m interested in, but the ethos of looking to the past came from two places. First, there was my former boss [Mother Jones editor] David Corn, who said, “the news is what people have forgotten, not just what people don’t know yet.” I think that with journalists, there’s a natural tendency to privilege new information at the expense of old information, without recognizing sometimes that readers may not have that full context.

Then there was my friend and former colleague Ta-Nehisi Coates, and I just really admired the way that he used to excavate history to talk about the present. I came to think of it as like a map. History is a map: it’s how we locate ourselves, and we follow it to the present. It can tell you where you might be going, and maybe where you should be going. I feel very fortunate that we have so many tremendous historians doing the work to build the sort of cartography of the American past that I followed in the process of writing this book. That’s basically the philosophy behind it: to try and give readers a sense of where we came from, so we know why we are where we are.

One example where this method is clearly applied is the essay “The Jewish Divide,” where you situate debates today among the American Jewish community—about liberalism, about American democracy—in the context of the American Jewish debate over slavery. I appreciated this piece, and not just because I’m cited in it, but because it tells the honest story of the struggle between Jews who were in favor of slavery and Jews who weren’t. This isn’t the comforting mythology that American Jews sometimes tell ourselves about our role in abolition and civil rights, but I thought it actually honored those who chose right all the more. After all, if the correct course was obvious, and everyone in the community was already doing it, what exactly was so courageous about championing it?

In this respect, the essay has one anecdote which serves as its frame: a controversy between two rabbis over abolition, one for and one against. I’d never heard of them before reading your book. Are there any other things that are not in the essay—stuff that you came across when you were researching the Jewish divide over slavery—that you wish more people knew about?

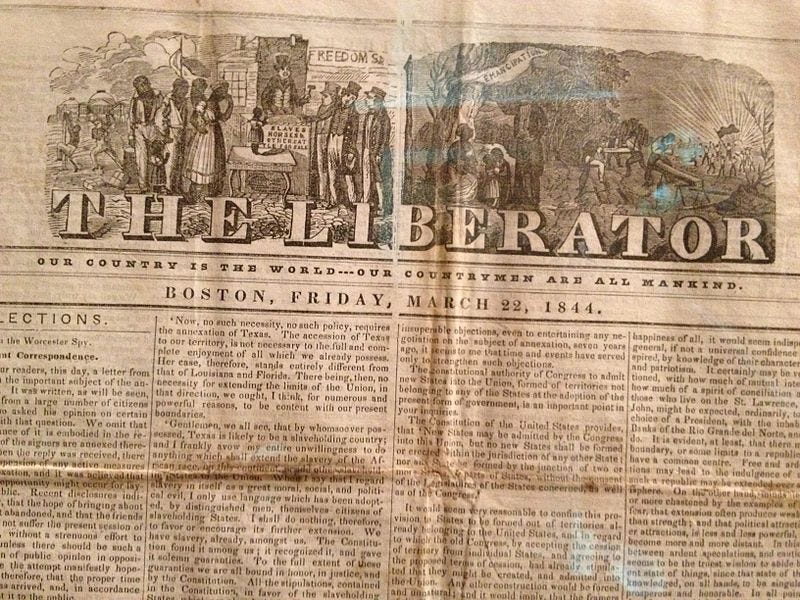

Oh, yeah, there’s a great anthology called Jews in the Civil War and it’s so fascinating. When I was looking for people to illustrate this divide, I found so many interesting examples. There’s a story in there about a Jew who rides with John Brown as he’s participating in these violent conflicts in Kansas over slavery. You could see this being a TV series. There’s a Jew who worked for The Liberator. At the same time, because of the nature of the migration of Jews to the United States, there are a lot of Jews in the South and they have come to accept the color line as a fact of American society, which is much more accepting of them than Europe was. And then there are actual Jewish senators who draw antisemitic attacks from the abolitionists who are otherwise right on the major issue of the day. [YR: Early on, the essay cites some eyebrow-raising examples of antisemitic attacks leveled by noted abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison.]

It’s just so interesting to me because the debate in the Jewish community over abolition very much mirrors the sort of debate that is happening in America over the Civil War, which is this question of what does it mean to have a democracy? Who is included?

I feel like it’s a part of Jewish history that is generally not discussed for some of the reasons you mentioned. It doesn’t paint the Jewish community in a totally favorable light. But what it does do, in my view, is that it demystifies this myth of American Jews having some sort of supernatural quality, either in a negative or positive way. These are just people who are acting according to what they believe their values and interests are and should be. That mirrors the larger conflict in the United States, but it also shapes the kind of Jewish pluralism that emerges from it.

So it was a lot of fun to look at these areas of Civil War and Reconstruction that I have typically written about in other contexts and look specifically at the Jewish community’s experience of these conflicts, and also to hopefully show people something new that they were not aware of.

In a certain sense, we come in after these questions were settled, or so we think. And so we don’t actually know how we got here. And sometimes that means we forget some of the values or the way to express those values that were needed to win that argument in the first place.

Right.

As its name implies, “The Jewish Divide” is about divisions: among American Jews, among Israeli Jews, between Americans and Israeli Jews, and also between the outlooks of the American right and left towards the Jewish people. And the essay engages in criticism of pretty much everybody. Your own sympathies are clear, but you also don’t shy away from critiquing those you identify with both ideologically and religiously. At points, you critique the Jewish community and our approach to Israel—obviously, the right-wing approach to Israel, but also to an extent the traditional left-wing Jewish approach to Israel. And then you also talk about the progressive left and its approach to antisemitism and critique that as well, writing that “a left that treats anti-Semitism the way the American right treats racism, as a largely imaginary phenomenon exaggerated by bad-faith actors, is a left that has failed to oppose bigotry in all its forms.”

This interests me tremendously whenever I see any writer doing it, because it’s unusual, necessary, and hard. Our own communities are the ones that are most likely to listen to us, which is why this kind of criticism can be the most important. But voicing it is also agonizing. To be heard, you need to speak from a place of love and genuine concern, not self-righteousness and superiority. And you need to somehow convey that in words. And so I’m curious, when you write criticism of communities you identify with, whether it’s talking about the American Jewish community or the progressive community in the United States, how do you approach that?

I struggle with it. I must have rewritten that paragraph 30 million times. I think it’s hard for everyone to criticize the people that they align with, especially in the era of social media, because I think people rationally understand themselves as being part of a community. And if you criticize that community publicly, you might get excommunicated, in which case, you have no protection.

As I mention in the book, this is one reason why I respect Never Trump conservatives. They’re an easy target for liberals because of their past records, but I consider them very brave precisely because to formally excommunicate yourself in that way is to relinquish your friends, your community, and your financial opportunities, and I think people are way too glib about this. “You get slots on MSNBC!” That’s not a really a replacement for community, for belonging. And so I tried very hard to be precise in that piece. I’m sure there are flaws in it. I’m sure that there there will be criticisms, and I understand that and that’s fair.

“Antisemitism … is not something that is inherent to right or left, because it so predates the modern conception of both, and is such a part of the Western intellectual inheritance. It’s just not something that you can immunize yourself from as a result of having correct beliefs.”

I think that in particular when it comes to antisemitism, it’s always important to maintain an understanding that it is not something that is inherent to right or left, because it so predates the modern conception of both, and is such a part of the Western intellectual inheritance. It’s just not something that you can immunize yourself from as a result of having correct beliefs. I wanted to ensure that people understood not to think, “if I support Israel, that means I’m not an antisemite,” or “I am a big left winger, that means it’s impossible for me to be antisemitic, because I oppose bigotry, not like those other guys.”

Obviously, you could write an entire book about that alone. But that was one of the arguments I wanted to make sure came across in the book.

I had a question about exactly this. In the introduction to your essay on Louis Farrakhan and the leaders of the Women’s March, “The Cruelty of Conspiracy,” you write that it’s a mistake to try to process antisemitism in contemporary political or ideological terms. It doesn’t come from socialism, or capitalism, or Christianity, or Islam or whoever, because antisemitism was around long before any of those movements existed. And you illustrate this very well, as usual, with historical citations that make this point inescapable. But if antisemitism doesn’t come from any of these movements that later incorporated and reflected it, what in your view do you think it actually comes from?

There’s a historian named David Nirenberg who has a book called Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition, which is just a really fascinating overview of anti-Judaism as an ideology from the ancient world to the present. And in it, you’ve got Greek writers in Alexandria, Egypt, writing things that sound like alt-right shitposts from 2015. It sort of blows your mind, like, how is this this old? It’s kind of like the idea of race—it’s a weird historical accident that has come to define large parts of our history. As with racism, I don’t think it is an inevitable part of our society. But I do think that it’s hard to understand how to extract ourselves from that intellectual prison without understanding how we got there in the first place.

We’ve talked about this before, but you’ve had a pretty interesting life and actually experienced some interesting antisemitism yourself. How has that informed and shaped your thinking?

My father worked for the State Department, and he was stationed in Italy for six years in a period of my childhood. And I think my first memory of encountering antisemitism is sort of a funny one, so I’ll tell it. I must have been seven years old, and my parents were sending me to this karate place in Rome. And this lady was like, “Qui si fa il karate come voleva Jesu Christo,” which means, “Here we do karate as Jesus Christ wanted!”

[laughs]

Which even at seven, I was like, you know, I don’t think Jesus had a lot to do with karate, but that’s just me.

Growing up in that kind of environment, there were just assumptions about Jews and Jesus, that we’re all very familiar with, that you encounter in your daily life. If you are an American Jew and you’ve lived most of your life in the United States, and you are not Orthodox—the trappings of Judaism are not visible on you—it is possible to go through life in America and think that antisemitism is not a big deal, and nobody ever encounters it. But I encountered it when I was a kid, in part because of where I lived. And it certainly shaped my assumptions about how serious it is and how much it lingers in the rest of the world, even though it might not for people who attend Temple Sinai in Washington, DC.

I have one Israel question that I will impose on you. Something that I really liked in “The Jewish Divide” essay was a very simple passage that probably felt unremarkable to you. You write that “Most American Jews support Israel but disapprove both of the current Israeli government and of Trump’s policies on Israel; a foreign policy toward Israel that catered to the preferences of the majority of American Jews would be significantly to the left of the one that exists today.”

This is one of those true things that is self-evident to people who know anything about the Jewish community, but is almost entirely absent from the public discourse of people talking about the Jewish community. So you get these constant invocations of something like the “Jewish Lobby” or Jewish political influence, as though (a) most Jews can agree on anything, and (b) to the extent that those Jews agree on something like Israel, that agreement is reflected in the non-Jewish policy consensus, when it almost certainly is not. In reality, as you write in the piece, American Jews are much more critical of Israel, and much more supportive of territorial compromise with the Palestinians, than American gentiles. We have polling data that shows this. And yet this refuses to penetrate.

This is a rant of mine, but the idea that the 2% of America that’s Jewish controls America’s Israel policy, rather than the 98% of Americans who are not, is not just problematic and conspiratorial, it’s also just obviously wrong, and poor political analysis. Yet this assumption sort of shambles on zombie-like, among both Israel supporters and critics. And this has really bad consequences for Jewish people who get spoken over and punished for a fantasy version of themselves that doesn’t exist.

I think that’s right.

I feel like I’ve been banging my head against this wall for some time in my own writing, and so was wondering, how does one break through? How does a minority group that is very small, by definition, get a majority to see itself as it is, rather than as it’s constructed?

I think that part of the issue here is that there is a moral force in being able to speak in the voice of American Jewry. And so both [non-Jewish] people who are critical of Israel and the occupation, and people who are uncritically supportive of Israel, want to be able to say that they are speaking with the voice of the Jewish people. And we know that [laughs] that voice is a cacophony of varied opinions. And so it is not really possible to say that we all speak with one voice.

I think the length and seeming interminability of the occupation has understandably created a large amount of anguish among American Jews, regardless of their position on the subject, because they want to see the Palestinians have full political rights, and they do not want to see them suffer. So there is a sort of political argument over who gets to speak for American Jews that often just ignores the complexity of how American Jews actually feel on the subject. And so in the piece, I was trying to communicate that that complexity exists, without substituting my voice and my position, which I know is a very left-wing position for other people, and which is why I relied substantially on public opinion surveys, because I didn’t want to make that mistake of saying, “I am speaking for American Jews here and my view is everyone else’s view.”

OK, here’s a less heavy question. You signed a bunch of copies of your book and posted a picture of it. Most people look at that photo and notice stuff on the bookshelf and things like that. I noticed your Hebrew tattoo. Can I ask what the story is behind it?

So I can talk about it a little bit. I will say that it is a Torah verse [from Jeremiah] that has a specific emotional meaning for me, and I got it after wading through interpretations of Jewish law regarding tattoos, and concluding that the prohibition applied to the names of deities and not necessarily inscribing on the skin itself. Now, I know that’s controversial. But that’s how I justified it to myself.

Yeah, there’s lots of folk mythology about about tattoos, like, “if you have a tattoo you can’t be buried in a Jewish cemetery,” which is nonsense. Speaking of folk mythology, in the book, there’s this parenthetical line that I love about the blood libel [the ancient accusation that Jews used gentile blood in their rituals] which simply says, “not that it matters to antisemites, but blood isn’t kosher.”

Right. It’s one of the things that always drives you crazy—the whole concept of the blood libel is impossible, just as a religious tenet, because we can’t consume blood. It’s an absurdity, but a terrible and unfortunate one.

It’s both funny and morbid and gets to the question of whether one can laugh about some of this stuff.

If we couldn’t, what would we laugh about?

Exactly. That conveniently brings me to my final question, which is about your outlook. You write about the darker side of the American story and you also write about people who fought against it. How do you maintain your optimism and your vision for the future while doing this?

There’s two ways. One is that I find a lot of inspiration in the people who were brave enough to speak out against the injustices described in the book at the time, people who were willing to tell the truth, at a time when society was unwilling or was not prepared to accept that truth. But also, I am humbled by the sacrifices of people who came before me to make sure that I could live the life that I live. I’m speaking specifically here about my grandparents and my parents. But I also mean that in a broader sense of the people who fought to ensure that I could enjoy the rights that I have, as a human being and as an American.

I think we all fall into sadness, sometimes, and hopelessness, but I feel like it would be a dishonor to them, if given what they faced I did not pick myself back up in those moments, because of everything that they had to go through to make sure that I could be where I am.

My thanks to Adam for taking the time out of his busy book tour to chat. If you liked what you read, you can find lots more like it in The Cruelty is the Point. And if you like conversations like these on topics like this, please be sure to subscribe to the newsletter: