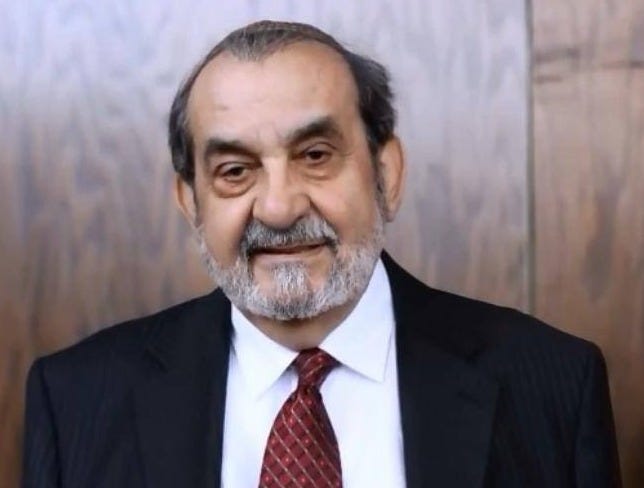

In Tribute to Velvel Pasternak, A Giant of Jewish Music

You've probably never heard of him, but few did more to preserve the Jewish musical tradition than Pasternak, who just passed away

On June 11, Velvel Pasternak passed away at the age of 85. You may not have heard of him, but you’ve probably heard the fruits of his work. That’s because arguably no person did more to collect, record, and promulgate the Jewish musical tradition than Pasternak. Over the course of 50 years, he published some 150 volumes of sheet music and recorded dozens of albums from every conceivable branch of the Jewish experience: Israeli music, cantorial music, Yiddish music, Ladino music, and Hasidic music. He even compiled one of the only collections of Holocaust-era music, Songs Never Silenced, which captured the compositions of partisans, concentration camp inmates, and others, and earned the approbation of Elie Wiesel.

It’s hard to conceive of now, but before Pasternak’s popular books, there was simply no easy way for students, schools, and band leaders to learn, teach, and perform countless Jewish melodies. Pasternak painstakingly committed those melodies to paper—whether it meant personally scouting out and annotating a given hasidic sect’s songs, or roping a bunch of members from their community into a studio to sing them for him.

Pasternak’s daughter Shira has described how her father stumbled into this unusual line of work:

One day in 1967, my father received a desperate phone call from a mother-of-the-bride in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. Her future son-in-law was importing yeshiva classmates from New York to dance at the wedding, but the closest Jewish bandleader, in Chicago, knew only two pieces of Jewish music — Dayenu and Hava Nagila — and they needed music for the band to play. In response to her request, my father transcribed 15 melodies, added accompaniment, and sent them off, earning a respectable wage of $25 for 2.5 hours of work. Several months later, he received a phone call from a family in Florida with a similar problem. He transcribed a selection of songs for them as well — but this time, he kept a copy. Soon Jewish band leaders from all over the country were requesting transcriptions of Jewish music, which he sent them for free.

Realizing that there was a need for books of Hasidic music with melody lines and chords, my father compiled an anthology entitled Songs of the Chassidim, but had trouble finding a publisher. To prove that there was a market, he sent out a pre-publication offer to a list of cantors and musicians. “Did you ever hear a piece of Jewish music and wish that someone would write it down?” he asked in his cover letter. The 300 advance orders that he received proved that there was interest in the book, which was published by Bloch Publishing in 1968.

The rest, as they say, is history.

Pasternak had an illustrious career not only as a compiler and popularizer of Jewish music, but as a lecturer and one-stop shop for all questions about it. He was a friend of my father, a synagogue rabbi, and spoke at our congregation on occasion. He was also happy to field random queries from me about Jewish musical practice and history. At the time, I didn’t quite appreciate how remarkable and generous it was for a scholar to take the time to answer the emails of a random college kid, but my sense is that this is how Pasternak unpretentiously conducted himself with his many respondents.

In tribute to his memory, I thought I’d share one of Pasternak’s more memorable replies to my inquiries. I’d posed to him one of the great unsolved mysteries of Jewish liturgical music: Why do most congregations switch tunes midway through the Sabbath song Lecha Dodi?

For reference: Lecha Dodi is a 16th-century hymn sung on Friday night to welcome the Shabbat. It contains 9 stanzas, and many congregations change tunes when they arrive at the 6th one. I had never heard a good explanation for this custom, so figured I’d ask the expert. Pasternak, naturally, had spent some time investigating this very question, and he replied:

I spent a year researching this … got all kinds of explanations. The only one that was plausible was given to me by the Pittsburger Rebbe OBM [of blessed memory]. He said in Yiddish: “Shoyn genug genidzet mit dem ershtn nigun.” (Ask your father to translate.) This is most probably the correct reason.

Loosely translated, that means: “They got tired of the first tune.”

May his memory—and his music—be a blessing.

If you liked this post, please be sure to subscribe to get future installments directly in your inbox:

Questions? Comments? Jewish music recommendations? I’d love to hear from you. Reply to this email, or drop me a line at yrosenberg@tabletmag.com. You can also find me on Twitter and Facebook. And be sure to tell your friends about this newsletter!